(Note: These exchanges are now complete. There is a Table of Contents to the discussion now available.)

Update: Daniel has posted a reply below.

When I have these kinds of exchanges on the blog, I really try to let the other person have the last word. After all, I have home field advantage here. I was absolutely ready to move on to my last part of this ongoing exchange with my friend Daniel Bastian in response to his Facebook post about his Atheism.

Last week, I wrote a post trying to give a cursory response to some of his claims about the Bible and miracles. Daniel wrote a response, posted a couple of days ago. I offered a brief response to his critique of my view of miracles. I was really eager to get back to writing about other things.

But it seems I can’t. Not yet.

I’m starting seminary back up this Fall, not simply because I’m interested in all the “knowledge” about the Bible, but because I feel I actually have a (pastoral?) concern for the spiritual well-being of people. I care a lot about what people might see on this blog, and I care that they are able to receive these things in ways that will be ultimately helpful to them.

And I fear that his post, at least for Christians not well-read in these issues, will cloud the waters more than clear them. Don’t get me wrong. Christians should wrestle with what Daniel has written in earlier posts, especially when it comes to the more abstract philosophical concerns of God’s existence and work in this world. These are things that don’t have easy or even clear responses by Christians. I’m not worried about Christians having restless nights or days as they wrestle with legitimate difficulties in the seeming difference between what they believe about God and the way the world seems to be.

But, when it comes to the Bible and the Resurrection, I don’t think we are on as shaky ground as Daniel makes it seem. Let’s discuss.

Before I begin, normal readers of this blog need to know that this is a long one. Probably the longest blog post I’ve ever written and posted in one chunk. This one post has a word count equal to over a week and a half of usual posts on this blog. And so, if you don’t have the time, I’ll link to a couple of articles that you should read if you can’t read anything else today:

- How Can the Bible be Authoritative? by N.T. Wright

- Christian Origins and the Resurrection of Jesus: The Resurrection of Jesus as a Historical Problem by N.T. Wright

- Jesus’ Resurrection and Christian Origins by N.T. Wright (a similar article to the previous one, but still good)

- “Can We Trust the Gospels?” by John Drane, an excerpt from his excellent Introducing the New Testament

- “The Resurrection” by John Drane, also from Introducing the New Testament

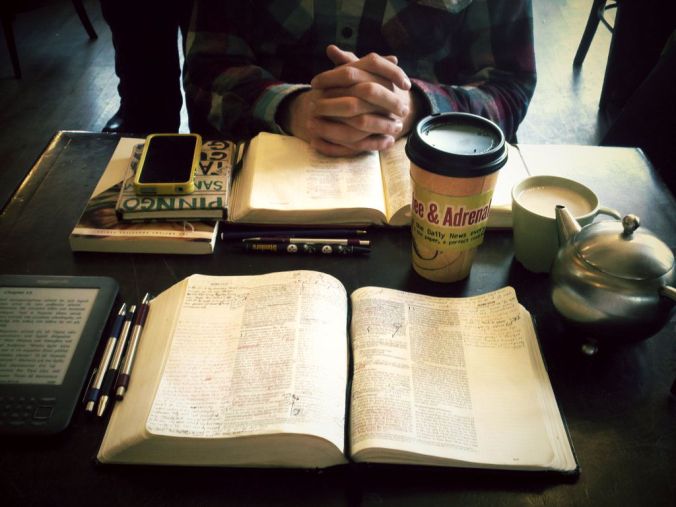

Okay. Grab some coffee, and let’s go.

Sincerely Wrong

In this first part, we’re going to hit some of Daniel’s points that were simply, clearly, flat-out incorrect. I don’t think that Daniel meant to get these things wrong, but they need to be corrected. I will also use each of these points as a launching point to talk of other, broader, more methodological concerns that touch on his other points.

“Q”, the Synoptic Problem, & Ancient “Lying”

Daniel thinks I purposefully omitted some necessary information. I was trying to not get into the biblical studies weeds, especially when I was also trying to discuss Miracles, and History, but apparently Daniel thinks this is especially important. For the record, I’ve not “hidden” or shied away from textual criticism and “Q”. Last summer, I taught a Bible Survey class at my church and talked at length about this.

The book of Mark is believed by most scholars to be the first Gospel written. Something like over 80% of it is reproduced nearly verbatim in both Matthew and Luke. Mark seems to have been the main source from which they built their Gospels. But there is other material that Matthew and Luke have in common that’s not in Mark. It’s some unnamed “source” that scholars started referring to as “Q” (for the German word for “source”. German scholars are known for their creativity).

This has long been known, and isn’t really a source of contention among scholars. In short: it’s not that big of a deal, yet Daniel thinks it is. But it’s only a problem if the original authors were intending to write a modernist historical account using modern historical methods.

But no. They used many sources in their writing. In fact, Luke explicitly says that he does. This hasn’t been hidden, secret, just recently discovered, or anything that the writers and later commentators thought was a problem or undermined to the integrity of the writings.

Daniel seems to have a conception of “source” that means it’s something that’s added later. But when scholars say that there are many “sources” behind the text, they are often referring to it in the same way that Mark is a “source” for Matthew and Luke: an earlier tradition or piece of writing that is present as the main new piece is being written.

Perhaps Daniel is talking about a “redaction”. That would be a later addition, though textual critics are quite well aware of what sections of Scripture those are, and they are nearly all theologically inconsequential.

But when we talk about “sources” of the Gospels, we are talking about earlier traditions, stories, and writings even closer to the original events than the writing in front of us. If anything, Matthew and Luke’s use of Mark speaks to the value they placed on it as a source in the first place–not some dastardly scheme to fool everyone or bolster their own claims. If that were the case, they could have easily simply cut Mark from the canon altogether.

Daniel so clearly imposes an unnecessary western, modernist historical ethic on the gospels. They are not overly concerned with “proving” the Resurrection. It is simply stated, not even over-dramatically or especially embellished (like the baptism and crucifixion scenes arguably are). Multiple sourcing was not a problem in the ancient world. Even the later additions to writers like Josephus (more on that later) were not done in a conspiratorial spirit, but rather trying to offer a fuller sense that the original author may not have known, but was nonetheless believed to be true.

It was common to write in the name of others–not to fool anyone, but to honor those people or to try and speak in their voice. The Hebrew line that’s translated “A Psalm of David” can also mean “A Psalm in the spirit of David”. This was common. Building off of another’s work was seen to honor that work and show respect. Or, sometimes it was simply a pragmatic concern. Why re-invent the wheel? Luke had discovered other accounts of events and so, using Mark and Q as a base, wrote out the rest of his accounting like an investigative journalist.

So in the end, Daniel wants to paint this as some sort of blow to the integrity of these works when (1) these facts have been known all along, even by the earliest Christians (Daniel even quotes Origen bemoaning Mark’s geographical inconsistency), (2) they weren’t trying to meticulously build a “case” using modern historical standards for peer-review, they were simply telling the story to fill in the spaces for believers who had come to faith in Jesus based on verbal proclamations and letters, and (3) all of these writings are perfectly at home in the ancient world as reliable guides for the events of Jesus’ life–no one would have the concerns that Daniel has placed upon these texts.

My personal take on Q was that it was an “oral document” (though there’s no way to prove it). And, contrary to Daniel’s assertion, study after study has shown the reliability of ancient oral transmission. At the very least, no matter how many specifics would get lost or corrupted in transmission, the Resurrection would not be one of those “incidental” additions due to an accidentally transmission error.

Twenty witnesses to a car crash (or even later commentators on the witness testimony) might indeed walk away with radically different takes on the details of the events, but they will all nevertheless have, as the center of their accounting, that their was indeed a car crash–an event that inspired this testimony in the first place.

And so, as Daniel reads this, I hope his biggest take-away is this: no matter the details of any other part of the gospels, what was central to the original Christian proclamation was this: Christ came, he died, and he rose again. The rest literally is just details.

The Resurrection is the point. It is the key to Christianity. If it is false, everything else is false, no matter how well-preserved the Scriptures are. If it is true, none of the other contradictions, textual critiques, or historical discrepancies make Christianity any less than the ultimate and final statement on reality and its renewal.

Daniel may take issue with other contradictions, geographical errors, or odd events recounted, but in the end, the entire New Testament is all united in those core assertions of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. And before he responds to that statement, I would ask that he read at least one of the Resurrection pieces by Wright linked above and the Drane piece on Resurrection.

One final word on Mark: in all my study I’ve never heard anyone claim that “numerous errors about the social and religious customs” exist in Mark. I’d heard the geography stuff, but (if early writers were correct about a “Peter core” to the book) I had chalked this up to Peter both being uneducated and not having been originally from most of the places that the Gospel takes place. After all, Papias of Hierapolis wrote in the early 100’s “Mark, having become the transcriber of Peter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, whatsoever he remembered of the things said or done by Christ.” Mark’s “messiness” is nothing new.

But I will say this: Mark is full of completely unnecessary incidental details that usually accompany true, eyewitness accounts, like the feeding of the 5,00 taking place on “the green grass”, Jesus’ trial taking place on a “second floor“ with the High Priest, there being more than just the disciples’ own boat on the water during the storm Jesus calmed, and that Jesus, at that time, was “asleep on a cushion”, etc. A Google search can pull out a lot more. Even the scholars that think Mark was compiled from many, many sources believe that at least some of the sources are very, very early. Even if, as Papias put it, everything was out of order, the basic facts seem to be pretty accurate in the book.

The Gospel of John in the Bible

Daniel mentions in passing that the Gospel of John was “initially rejected for canonization by Church fathers”. There was one very small fringe group of heterodox Christians in Asia Minor that didn’t like the logos idea in the intro of John’s Gospel and rejected it.

Other than that, no other group or leaders ever argued against that Gospel being in the Bible, much less any “Church Fathers”. There was certainly lots of disagreement over 3 John and Revelation due to how unlikely it was that the John wrote those. Maybe Daniel means this.

Concerning John, though I usually go along with the consensus that it was the last gospel written–and pretty late at that–I must admit that I have been given pause by a minority scholarly opinion that says otherwise. This view believes John is in fact very, very early, likely written at the same time as Mark (or even before!). (Here’s a great defense of that view in a mainstream contemporary commentary.)

The “lateness” argument is usually based on two things: the conflict motif between Jews and Christians the assumption, and the assumption that exalted ideas about Jesus would only have come later after theological reflection among Christians.

However, the Gospel of John seems completely ignorant of any of the other Gospels, there was conflict with the Jews from Day 1 of Christianity (not just later on), the Gospel has no direct explicit temple destruction prophecy nor confirmation (which you would think would be in there if it was written in the 90s in the midst of Jew-Christian conflict, as most scholars think), and the whole “evolutionary” idea to theology is borne from a particular worldview and a set of assumptions–not from facts.

It seems to me that Chapters 2-20 of John were written all at once to a primarily Jewish Christian audience (with some other stories thrown in later, like the woman at the well), and the circulation was very small, probably just within Jerusalem. At a later time, the book was then prepared for a wider, Gentile audience by John’s church community (perhaps with his input). They added the first chapter (the logos introduction), Chapter 21 (to address ideas about John and Peter’s deaths), and some other “greek-ifying” elements for its wider circulation.

Philo & The Mythicists

In Daniel’s piece, there is also a mention of Philo of Alexandria and his use of the logos idea and (as Daniel says) the claim that Philo “documents a pre-Christian Jewish belief of a celestial being named: ‘Jesus’.”

First, Philo mentions the logos only a few times in his writings, and each time he refers to something different. Once, it’s the mind of God. Another, it’s the realm between God and man. Yet another, it’s human logic. It’s not a human. It’s never thought of as the Messiah. It’s very different from the Greek conception, which is the primary way in which it is employed by the writer(s) of John. Here’s a good, brief summary of all of this. Here’s another summary of the contrast:

(1) Philo’s Logos-Mediator was a metaphysical abstraction while the Logos of the New Testament is a specific, individual, historical person. Philo’s Logos is not a person or messiah or savior but a cosmic principle, postulated to solve various philosophical problems. (2) Given Philo’s commitment to Platonism and its disparagement of the body as a tomb of the soul, Philo could never have believed in anything like the Incarnation. Philo’s God could never make direct contact with matter. But the Jesus described in [the New Testament] not only becomes man but participates in a full range of all that is human, including temptation to sin. Philo would never have tolerated such thinking. (3) Philo’s Logos could never be described as the [New Testament] pictures Jesus: suffering, being tempted to sin, and dying. (4) The repeated stress in [the New Testament] of Jesus’ compassionate concern for His brethren (i.e., Christians) is incompatible with Philo’s view of the emotions.

Second, Philo’s logos ideas are based on pre-Philo Jewish thought connecting the logos to the Old Testament ideas of “Lady Wisdom” in Proverbs and the use of the “Word of the Lord” or the “Word of God”. Once again, these were never thought of as people, incarnations, or connected in any way to the Messiah. It was considered speculative theology and not Jewish dogma. The logos remained entirely a Greek idea that the Jews, in a sense, “played with” in their theology. It wasn’t central to Philo’s thought, or any other Jewish philosopher. This is why many scholars don’t think Christians were basing anything on Philo, but rather that both the Christians and Philo were borrowing the language of a common source.

Thirdly, let’s talk about this whole “Philo talking about Jesus” business. In one passage, Philo is making a poetic reference to a priest in Zechariah that is named “Joshua”. Because Philo–as did most Jews in that day–worked off of the Septuagint (a Greek version of the Old Testament), he used the Greek transliteration of the Hebrew name “Joshua”, which is–you guessed it–“Jesus”. In fact, if you look in the Septuagint, there’s an entire book of the Pentateuch called “Jesus”. And that’s because it’s the book that we know as “Joshua”.

Lastly, other than the agnostic scholar Bart Ehrman, Daniel spends most of this post filling it with arguments and quotes that come primarily from thinkers that are called “mythicists”. They are those that think that Jesus never existed in the first place. This is an opinion that hardly any professional and serious scholar holds. They may disagree about who this Jesus was, what he said, what he did, and how much we can answer those questions at all, but there is pretty universal agreement that Jesus was a historical person.

The reason I mention this here is that one of the greatest popularizers of this whole Philo nonsense is a mythicist named Richard Carrier who, yes, has a Ph.D. in ancient history, but isn’t really practicing his scholarship or research anywhere and has only a few writings that have appeared in peer-reviewed journals. Other than that, he writes on lots of blogs. Either way, I don’t know how we’re defining “scholarship”, but this is kind of loose.

But this is precisely the kind of source that a lot of Daniel’s points come from–probably inadvertently (although he does say that he will read “with great interest” Carrier’s new book. Of all the things I might think about what Daniel believes, I would never accuse him of intentionally trying to mislead.)

A lot of Carrier’s (and some of Daniel’s) arguments focus on the idea that the Jews were expecting a Messiah to come, be divine, die, and resurrect. If this were true, then one can say that Christianity was born out of this expectation, and that early Christians forced this idea on a random preacher, Jesus, when he never would have intended that. This view is in the extreme minority and garners very little support and respect. Even Ehrman, Daniel’s main source of scholarly credibility (and it certainly is a legitimate one!) has attacked Carrier on numerous occasions on this exact point.

There is absolutely no evidence that there was any Messianic expectation of death at the hands of pagans and subsequent resurrection. Some mythicists try to find odd places (like Philo) to find a smoking gun, but they are the only ones. There were lots of failed messiahs in ancient Israel. Lots of them. None of the Jews decided to form any idea about them being resurrected. This is one of the reasons why (as Daniel points out) there was so much immediate conflict between Jews and Christians. And yet, as I said in my other piece, no one who could have clearly countered the claims of the Resurrection did so.

Yes, lots of non-Christians thought the idea was silly (also lending to its lack of immediate literary attestation), but no one was able to produce a body, offer proof, or stop this movement from forming, even though there would have been many people not only with the ability to do so, but great incentive as well. There was not just a Resurrection proclamation, but empty tomb evidence.

Documented History & Gospel Weirdness

Speaking of mythicists, Daniel takes from the father of mythicism, John Remsburg, a list of all the writers that lived during or within a century of Jesus to say that this time was the most well-documented time in the ancient world. I had asked him to provide this citation because I didn’t know what he was getting at. Now I know.

Originally, I wondered if he was trying to say that we have more surviving documentation from this time than at most any other. That’s why I was skeptical. And Indeed, he was simply saying that we had more people then that were writing stuff down than we’ve had at many other points in history–not necessarily that those documents have all survived.

I really tried to find a percentage of how many works scholars think we have lost from that time period, and I couldn’t find an exact number. The estimated percentage I could find of those writings we still have ranged from .3% to 3%. So yes, a lot of people were writing back then. We’ve lost nearly all of those writings. The fact that a rural itinerant preacher, who would’ve been on the radar of a couple of regional governors for a week before being killed, got any play in ancient writings–much less writings that have survived until now–is pretty remarkable.

Also, I’ve hesitated mentioning this because the textual history is so complex and there’s a lot of disagreement among scholars on these texts, but there are also fragmented sayings of Jesus found in Egypt that date in the early 200s, that are most certainly copies of even earlier texts, which hints at the speed and distance the words of Christ traveled.

There’s also the Babylonian Talmud which contains references to Jesus having been a wizard and done miraculous things (by way of an evil power), and that there was the claim he was born of a virgin. Like I said, especially with the Talmud, no one knows for sure how early it is, but there’s at least the possibility that even Jews were aware of the miracles he was doing and that were attributed to him.

Lastly (for this argument), Daniel brings up some of the crazy supernatural things at Jesus’ death that only two Gospels talk but no other Gospel nor other New Testament writing mentions: Mark’s sky turning dark and Matthew’s report of an earthquake, dead people rising, and the curtain in the temple being torn in two.

I’ll be honest with him: I have no idea. I’m fine with biblical authors adding non-historical items for thematic purposes, but even these events stretch how much the Gospel writers usually do this.

If it’s any encouragement, most Christian commentators are also left scratching their heads. As far as Mark’s darkness, I could see this being a “local darkness” rather than a “global darkness” if indeed it happened. As far as Matthew’s earthquake and rising dead, this would fit thematically with the Jewish emphasis of Matthew and how this messianic death is a rolling back of the original Creative act. But in the end, I don’t know.

But, I will point out (and this is often missed by critics), the fact that it’s not mentioned anywhere else, even very late writings, goes to show how much the early church had no problems with these things being there. Daniel–and others–want to point out contradictions, changing narrative chronologies and geographical inconsistencies as if they were the first to notice these. But no–early Christians, and even early Scriptural writers, were also aware yet still had no problem keeping these things in without extra comment.

This either means that they (1) were especially confident in their historicity and needed no extra comment or defense, or (2) (what I think is more likely) they had a particular view of the Bible, writing, and telling stories that would not have precluded non-historical elements being placed in the story while still seeing authoritative truth in the text.

In other words, perhaps we’re trying to place an unreasonable modernist expectation on the text to create problems where the original audience would have found none.

It also means that, most importantly, other writers/redactors/commentators of Scripture didn’t view this “other stuff” as the most essential parts of the story. Indeed, the earliest Christian proclamation centered around Jesus’ words and Resurrection, not this odd stuff happening at Christ’s death.

Josephus & Other references outside the Bible

Oh Josephus. A favorite of Christian apologists. In Daniel’s post, he says that Christians “forged” Josephus. This is an intentionally provacative stretch of wording. Most every scholar thinks the “nucleus” (as they call it) of Josephus’ references to Jesus (and John the Baptist and James the brother of Jesus) are original. As I said earlier, early Christians simply expanded what Josephus wrote, trying to add a fuller sense than Josephus would have known or believed. Yes, this isn’t good, modern methodology. Yes, today this makes us predisposed to skepticism on other references. But, in the ancient world, this was normal practice.

There is no evidence that there was blatant, widespread “forgery” of texts as Daniel puts it. In fact, many of the ancient world’s text, including Josephus’ works were actually preserved by the Christians. They were in their care. If they were trying to egregiously fool anyone by adding stuff, surely they could have added a whole lot more than they did. The additions into Josephus, while certainly using exalted language for Jesus, do not form any “new” basis for “new” ideas Christians would have had. It wasn’t an attempt to “fool” or lie.

Daniel (and others) make a big deal that neither Jesus nor Christians are “mentioned” outside the Bible until the early 100s. But these Roman “mentions” are not just about the state of Christianity at the time of the writing, but also the past. Tacitus and Seutonius don’t simply talk about Christians in their own day and time (as if they had just recently popped up), but are talking about them being persecuted by Nero around 60CE–less than thirty years after Jesus’ death and Resurrection, and more than 1500 miles away from Jerusalem. The Tacitus account in particular shows us:

(i) that there were a sizable number of Christians in Rome at the time, (ii) that it was possible to distinguish between Christians and Jews in Rome, and (iii) that at the time pagans made a connection between Christianity in Rome and its origin in Judea.

There was also accounts of persecution under Domitian around 90CE. Though the size of this persecution is contested, it is nonetheless true that, to some extent, Christian were around and big enough to cause problems in Asia Minor before the end of the 1st century.

Just because the writing itself doesn’t appear until the 100s, that does not mean it doesn’t “count” towards our understanding of earlier events in Christianity.

Life Expectancy & Eyewitness Reportage

Daniel writes, “If I recall, the average life expectancy of 1st century Roman Empire was ~29 years of age (the absurdly high IMR at the time pulls this average down).” Yeah, the infant death rate does pull it down. WAY down. So far down that “29” is not a relevant number to this discussion. One simple Google search on the matter brought me to this Wikipedia page, which helpfully pointed out that if you made it age 15, your life expectancy jumped to 52! Way different from the “29” Daniel mentioned.

And we have to remember, that even though this is the case, this is still an average. Ancient historians mention ages for individuals and even among entire groups that even exceed 100. More on this here.

Again, most every serious scholar believes that most of the traditions behind the biblical texts go back to eyewitness accounts, stories, and/or traditions, even if they were not the ones that eventually wrote them down.

At worst, even if Daniel were right and there was decades of silence with no tradition, preaching, or eyewitness accounts circulating before these writings popped up out of nowhere half a century after the events they describe, of all the things that would have been lost over those silent years–all the details, names, locations, etc.–the central idea of a dead man getting up again would not be one of those incidental little transmission errors.

At the core of the gospels are accurate representations of what life looked like among the early 1st-century Palestinian people. Life in the region looked very different by the end of that century. And yet, none of our writings (except Revelation) reflect being written in this radically different environment. Unless you approach the texts with assumptions already in place, there is no reason to believe that the core of all of these texts are anything other than eyewitness accounts–maybe arranged in a particular order for thematic (not conspiratorial) purposes–but eyewitness nonetheless.

A quick example: Luke describes Paul’s recounting of his conversion experience several times through the book of Acts. Every single one of the recountings is different. Now, if an incredibly detailed and careful writer like Luke felt comfortable adapting the details of that story to different audiences within the same piece of writing–and still consider his own piece an “orderly account” (and the early Church agreed with him)–how much more acceptable might it have been to have Gospels that do the same thing?

Once again, I think Daniel is imposing wrong standards on the Bible, unable to shake the fog of modernist thinking from his assessment of these texts.

Something skeptics seem to forget: if the early writers were setting out to craft a narrative out of nearly nothing, they did a really crappy job. The fact that the inconsistencies, contradictions, difficulties were all known and accepted by the earliest Christians must offer us a hint that something else was going on other than a vast “sincere, but wrong” reinterpretation of this Jesus guy. Early Church leaders had lots of time and ability to “smooth things out”, but they never did, in any fundamental way. The texts simply don’t read like it, and their development does not reflect this at all.

Daniel then throws out the good old argument that the texts went through “centuries” of edits and revisions. This is severely misleading. In Bruce Metzger’s and Bart Ehrman’s seminal work, Text of the New Testament: It’s Transmission, Corruption, and Restoration, the authors say:

Even though many of the details [of textual history] are shrouded in mystery, it is possible to trace the general outline of this history and to evaluate the textual character of the major text types attested among our surviving Witnesses…. The complications notwithstanding, most textual critics would agree that our manuscripts for each biblical book…in one way or another go back to a text that was produced–either authored or edited–and published at some specific time and place and that it is this “final published” edition that served as the basis for all later copies that the textual critic is trying to reconstruct.

In other words, there is a primary “core text” behind the text we have, and throughout Metzger and Ehrman’s book, there is an optimism that we can have high confidence in at least the general sense of the writing. We know pretty precisely what “edits and revisions” have been made, and they are not anything like the Dan Brown conspiracy situation to which Daniel is subtly (even if unintentionally) alluding.

The earliest Christians were the first textual critics, with nearly all of them comparing manuscripts and wrestling through variants. They were determined to do the painstaking work to get to the truest core of the text, not simply “changing things” to fit their own ideas. Textual variants don’t work that way. Even when doctrinal things were added or removed (almost always by rogue scribes, not church leaders), they were usually based on other Scriptural ideas, not entirely new doctrines being thrown in or core ideas being taken out.

And (in our well-documented history of variants, including doctrinally-based ones), they were almost always on minor theological issues. Never in our entire history of textual transmission (that I know of, at least) do you have a body of texts that don’t have Jesus, his life, his death, and his Resurrection. That is simply not how textual variants occur, and to imply otherwise is either incredibly dishonest or speaking beyond one’s own knowledge.

There’s an incredible optimism in textual criticism that, though no text is “one continuous stream from one individual”, we can at least know what its original, intended contours were. To suggest that the text can get corrupted to the point where we can’t is very ill-informed, and using the term “edits” and “revisions” is a huge stretch. “Variants” is the technical term here, and even so, we’re talking about–at worst–a phrase here or there that is omitted or added, a paraphrase of an especially wordy set of lines, or harmonizing between gospels. And hardly any of these variants are of any doctrinal or theological import at any level. There weren’t entirely new “editions” or “revisions” of entire books stretching down through the centuries. The vast, vast majority of variants come from errors, not intentional doctrinal moves by scribes.

St. Paul: a clarification & a story

Daniel apparently thought that in my earlier post I was implying that people think Paul isn’t a real person (at least I think that’s how he took what I was saying). Rather, I had a very different point I tried to make when referring to Paul. The Apostle Paul caused more problems and had more reason to be cited by Roman writers than Jesus, and yet was not. Daniel cited early Christian writers who refer to Paul, writing later than the Roman sources for Jesus. He actually was making my point.

People make a big deal over Roman historians not writing more about Jesus, but I was saying that Roman historians had no reason to write about Jesus. In fact, had more reason to talk about Paul, and yet they did not.

This also highlights the different evidentiary standards used by many skeptics for Paul and Jesus. In spite of no attestation of Paul outside the Bible, people accept way more at face value about his life, work, and beliefs than they do about Jesus. Even apart from non-biblical attestation, we really can get a sense for the “real” Paul and Jesus based solely on the New Testament.

I once attended a lecture by E.P. Sanders, one of the world’s foremost scholars on Paul. He described himself as a “liberal, secularized, modern Protestant” and does not shy away from any view of the New Testament no matter how much it flies in the face of traditional Christian thought. The lecture outlinined much of Paul’s thinking as shown in his letters, and at the end, this man at the forefront of “liberal” scholarship closed his binder of notes and said,

“at the end of the day–and I’ve tried to get around this any way I can–I’ve spent so much time with Paul, I feel like I know him through and through. And no matter how I try to look at it, I can’t come to any other conclusion than Paul really truly experienced something in his life. He really believed everything he wrote. And that bothers me. Because I don’t believe the things he believed. I haven’t experienced the things he seems to have experienced. And I don’t know that I ever will. But there’s not a doubt in my mind that Paul did. He really, really did.”

I’ve never forgotten that. And I think the same trust and understanding can be said for Jesus and the Gospels.

Laodiceans: a quickie

Contrary to Daniel’s assertion, there’s no such thing as a 1st century apocryphal letter to the Laodiceans. There’s one 4th century Latin manuscript that calls itself “Laodiceans”, but its contents are just a mashup of verses from Philippians. Some scholars think (and I agree) that Ephesians might be the actual letter to the Laodiceans that Paul references. This is because Ephesians seems to be written to a group of people Paul had never met, but Paul had spent several years in Ephesus and knew them very well. Ephesians looks like it was meant to be a circular letter, perhaps first sent to Laodicea, but the Ephesian copy perhaps became the most widely distributed. No one knows for sure.

Other religious texts & “myths”

I made a comment about how I don’t understand why skeptics like Daniel seem to “so easily write off” the biblical writings as historical sources. Daniel didn’t answer my question but simply said, in essence, “the same reason you disregard other religions’ texts”.

But here’s the thing: I don’t! I was talking about historical veracity; not theological. I may not believe the oil in the Maccabean lamps lasted as long as the story says it did, but that doesn’t mean that the books of the Maccabees are not incredibly valuable historically. The Quran and other religious writings are very important for speaking to a specific historical and cultural mindset. But even this value seems to be abandoned by over-reactive skeptics and fringe scholars. I don’t need extra-Qurannic attestation to believe that the Prophet really believed he had this vision and what effects it caused.

And this connects to Daniel’s reference to Sathya Sai Baba, an indian guru that Daniel cites as a modern example of a “myth in the making” right before our eyes.

First, as C.S. Lewis put it in the introduction to The Problem of Pain, being a Christian does not necessarily mean that you think every other religion or religious experience is wrong–it’s just that whenever they disagree with Christianity, we think Christianity is more correct. He says that all religions have the “camera lens”, as it were, turned on the same God and the same Truth; Christianity just believes their camera is the most “in focus” (because of Jesus’ revelation of God). Other faiths have many of the same contours and experiences as Christianity, but because their understanding does not include Jesus, these similarities are mere shadows of the fullness and clarity of the truth.

I’ve mentioned in another post that the Bible talks about many individuals that are outside the People of God that access and experience the spiritual realm in various ways. I’m not speaking to whether or not Sathya Sai Baba is genuinely one of those people, just that whether or not he is is of no consequence because the key to the Christian faith is not having the market cornered on spiritual experience, but is instead the Resurrection.

But to Daniel’s point more specifically: there are so many variables here that make this fundamentally different. Contemporary analogies will always fail because of of technology that makes “myth” (if that’s what this is) spread faster now than in earlier epochs (and ironically, I had never heard of this guy before Daniel mentioned him).

As mentioned earlier, even the Babylonian Talmud calls Jesus a sorcerer who did miraculous things like heal people–and yet they write him off. Miracles are not the driving force behind lasting “myth-making” movements (all three of those phrases are very important to what I’m saying) that continue to grow long after the central individual’s death. Preaching is not the driving force either, nor is conquest (Ghengis Khan’s “divine” status died with him, especially after his sons lost all he gained).

The key, once again, is Resurrection.

Whatever type of movement borne from Sathya Sai Baba’s life and teaching, it doesn’t and will not look anything like the development of Christianity in the 1st-century. It will not have the sustaining growth, diversity of ethnicity/geography/class/people, intellectual fortitude, and life-changing power that Christianity has. Groups of people believing seemingly crazy things about individuals and events is nothing new. Christianity is still an utterly unique historical occurrence, with no predecessor or antecedent. There is simply no similar analogy one can find.

The Wrong Kind of Bible?

I need to apologize to Daniel because I’m only now getting to what he says is the core of his main argument: that no matter how amazing the Bible seems to be, it’s a huge gulf to cross from claiming religious authority for a text and that being some proof that God is behind it.

In Daniel’s understanding, I’m more or less wasting my time defending this Bible stuff because in the end, it means nothing for what is actually convincing about God Himself (and then he goes on to pen another 5000 words in defense of all the “meaningless” stuff, but whatever, I get it. People don’t like being disagreed with).

First, I would refer Daniel to the single greatest resource on this I’ve ever read: N.T. Wright’s classic article How Can the Bible be Authoritative?. No matter what I say, Wright will address it better than me, but here goes my thoughts.

Daniel is kind (and intellectually clear) enough to give us very honest, unambiguous criteria by which he would find the Bible compelling. I don’t mean this as an insult, but he is quite open that he would like there to be the kind of religious text that we would easily write off as silly. He wants secret codes and eternal moral truths before humanity had “discovered them”. He wants scientific formulae within the text that unlock the powers of medicine and explanations for all our questions. Or, at least, a book that doesn’t look just so damn human, “uninspired”, and messy.

I think too many Christians would write his idea off too easily. Christians need to realize that our book doesn’t–in any way, really–look self-evidently “divine”. Too many defenses of the Bible simply try to make the Bible look like the kind of book that Daniel wants it to be. I grew up with Sunday School teachers telling me that the Bible talked about a round earth, microwaves, germ theory, relativity, and dinosaurs coexisting with humans. But it doesn’t, and the criticism remains.

My own personal take is that Daniel’s criteria are way too culturally conditioned by modernism, and he seems to be wanting a God that, after revealing Himself, looks a whole lot more like a giant “Daniel” in the sky than anything that would actually challenge any of his notions about reality or himself. I can imagine an artist saying that a truly “divine” Book would need to be the most stunning work of Beauty the world had ever known; a Psychologist saying it would need to unpack the secrets of the human psyche; a social worker or politician saying it would need to talk about how to order society such that peace and justice at all levels of society are established.

As the old saying goes: in the beginning, God created Man in His own image. Then, Man returned the favor.

It is a modernist assumption that has limited “Truth” to that that which corresponds to material reality. When that became the case, Science and History became the only vehicles for what was “true” in the world.

Christianity, however, believes that “Truth” is what corresponds to Ultimate reality. And in that case, art, poetry, myths, story, narrative, and ancient messy contradictory and geographically untrustworthy texts (and even seemingly silly ideas like God becoming human and dying) can be vehicles for “Truth”. As I’ve been saying all along, Daniel’s conception of reality is too “simplistic” to understand or conceive of how this book can be “true” in any ultimate sense.

I honestly don’t know what to say that would effectively adjust Daniel’s expectations of the Bible. I wish I did. The Bible does not look like the way he says it would need to look for him to believe what it says in that ultimate sense. So…conversation done, right?

All I can tell him (and any other skeptic) is that the God of Christianity is one that reveals himself among us. This idea of “revelation” seeps upwards from the mud and dirt of the world. As I said in a lecture I did a couple of years ago at my church on the Bible:

The Bible is not some book that stands above history and merely comments on it as time goes on. It is borne out of and is a product of its history and culture and by the time it gets to us, it is not very clean, perfect, or pristine. It carries with it the marks, hits, impacts, wounds, and scars of being written and handled by time-bound, enculturated individuals. This is where so many of our western, post-Enlightenment questions about manuscripts, translations, books being chosen or kicked out, archaeology, history and literalism come from. We have the preconceived notion that a truly “holy” book should be without its own set of marks, wounds, and scars.

But let me encourage you that the Jesus we worship is one that on his post-Resurrection body still carries the scars of the life he lived here on earth. And we may want to look at him and say “Jesus, those are blemishes–‘imperfections’ in your skin and your body.” But he will respond with “No, they are precisely the point! They are to show how far I will go and how messy I will let myself get just to reveal myself to you.” And though we have questions and frustrations with every History Channel special we watch, my hope is that we can walk away from those not abandoning or doubting our faith, but having new reasons to stand in awe of the God that traversed heaven and earth to know us and have us know Him.

I find that truth stunning, beautiful, and yes, compelling. It’s probably better for us that we have a messy compilation of stories and poems than a science textbook. But still, there’s some common ground here with Daniel.

Daniels says that a religious book is not proof of the divine, but rather it’s a claim. And you know what? I absolutely agree! This is why Daniel’s reference to ways that a religious text could suddenly be “awesome” enough to win him over is ultimately disingenuous, because his disbelief isn’t really about the book itself (as he said). But, this also a very Christian idea, as even Jesus and Christianity say that defending the Bible is not an ends in and of itself to the Divine (even though many modern fundamentalists act like this is the case).

Rather, defending the integrity of the New Testament is not seen as a proof for God, but it gets us closer to the Resurrection.

And ultimately, Christianity is not fundamentally about the book. It’s about the Resurrection. I’ll once more encourage Daniel (and anyone else reading this) to read N.T. Wright’s two wonderful essays on the historical case for the Resurrection (here and here), as well as John Drane’s treatment of it here.

Daniel said in his post:

What I think is much more likely (and this is the majority view of secular scholarship) is that an itinerant Galilean preacher came to Jerusalem, paid lip service about being a Messiah, got crucified for insurrection, and then his followers interpreted this colossal failure as some kind of spiritual success. These distortions then permeated into the annals of history as more and more people were won into the faith by emotionally moving tales of salvation, bodily renewal and guarantees of an elysian afterlife.

I hope reading this and reading the linked articles can show you this is not the case. The real majority scholarly opinion (religious and secular) is that from the earliest days after Jesus’ death, there was the belief that he had physically, bodily risen. Scholars disagree as to why the Christians thought that. But that’s what scholars generally believe; not this whole decades-later myth-development business.

Christopher Hitchens once said that the fact that women (people who could not have even testified in court at that time) were recorded as the first witnesses to the Resurrection (in every Gospel account, by the way), convinced him that something had to have happened on that Easter morning. He followed that by saying that his worldview dictated that it could not have been the bodily resurrection of Jesus. But something must have happened that day. Not decades or even weeks later. But that day.

That is an honest view that does justice to the evidence. Ultimately, I do not think Daniel’s reconstruction is consonant with anything looking like the conclusions of mainstream scholars past and present (even non-Christian ones), and instead relies too much on the theorizing of unscholarly mythicists. I wonder what reconstruction he would offer if he were to bring his opinions in line with scholarship, that from the earliest days of the Church, there was the belief in the physical, bodily Resurrection of Christ. What would he offer as the reason behind this?

I would challenge him to consider these things

Editor’s Note: I know this is really not fair to Daniel, but I’m going to request that any response he offers, he keeps to the comment section of this post and on Facebook. If he does, I’ll add a link to this post. Frankly, I’m really eager to move along to our final post, so Daniel can respond to that. If there is a general uproar over me seeming like I’m not being open to critique, I’ll reconsider this, but for now, I’d ask that this be the case.

Pingback: “New Testament Historicity: A Response” by Daniel Bastian [GUEST POST] | the long way home | Prodigal Paul

Paul,

I really enjoyed this piece. You actually dispute very little of the information I presented. Effectively you appear to simply contend that such details are not as important for the Christian faith as I seem to think. And this is perfectly reasonable. So I’m perfectly OK at this point with allowing the readers to form his or her own conclusions. Below I’ll just add some clarifying comments to areas where I think you misread me or are oversimplifying, and we’ll call it a day.

Paul: “And, contrary to Daniel’s assertion, study after study after study has shown the reliability of ancient oral transmission.”

What assertion? Here is what I said:

“Oral history is far less reliable than (independently attested) written history for the simple fact that oral words are more easily changed.”

Oral tradition is not a priori unreliable (so long as key criteria are met), just less reliable than written sources. This is uncontroversial and I stated nothing further in my piece.

Paul: “And one final word on Mark: In all my study I haven’t ever heard anything about “numerous errors about the social and religious customs” in Mark.”

This is common knowledge. Dale Martin discusses it in one of his first lectures in his intro course that I linked in my piece.

http://oyc.yale.edu/religious-studies/rlst-152

Paul: “I’d heard the geography stuff, but (if early writers were correct about a “Peter core” to the book) I had chalked this up to Peter both being uneducated and not having been originally from any of the places that the Gospel takes place (outside of rural Galilee, his hometown). After all, Papias of Hierapolis wrote in the early 100′s “Mark, having become the transcriber of Peter, wrote down accurately, though not in order, whatsoever he remembered of the things said or done by Christ.”

The details are a bit more complicated than this. Papias was a hearer (supposedly) of John the Presbyter (aka John the Elder), not to be confused with John the Apostle, and we don’t know specifically which sources (oral or written) he is referring to, in part because Papias is known only through the writings of the 4th Century Church historian Eusebius (who called Papias “a man of small intellect”). Papias does *not* speak explicitly about the canonical gospels. He gives descriptions of gospels which other writers like Irenaeus *later referred to* (CE 180) as canonical Mark and Matthew. All we have of Papias’ writings are what Eusebius quotes in his Church history, but this is what Eusebius quotes Papias as saying:

http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/text/papias.html

Eusebius quotes Papias as claiming that somebody named Mark wrote down the memoirs of Peter “not in any particular order”, but this does not fit any description of canonical Mark known to scholarship. It’s not a memoir, for example. It’s a highly literary construction following a complex, chiastic structure that is not the result of writing things down in random order as received from earlier sources.

The Ehrman link below talks about Papias, saying the same thing. Please skip to 35:16.

Ehrman on Papias:

Paul: “Daniel mentions in passing that the Gospel of John was “initially rejected for canonization by Church fathers”. There was one very small fringe group of heterodox Christians in Asia Minor that didn’t like the logos idea in John’s Gospel and rejected it. Other than that, no other group or leaders ever argued against that Gospel being in the Bible.”

Not true. In fact there was heated debate over John’s gospel at a number of councils. This is also discussed in the intro course by Dale Martin.

Paul: “and the whole “evolutionary” idea to theology is borne from a particular worldview, and not from facts.”

Not borne from a particular worldview but is a trend observed throughout history. The further from the supposed event you regress the more miraculous and embellished the stories about it become. This is what I stated in my piece and has been observed all across history, from Roswell to ancient battles like the Battle of Thermopylae to religious myths and folklore. Again, nothing controversial.

Paul: “This is why many scholars don’t think Christians were basing anything on Philo, but rather that both the Christians and Philo were borrowing the language of a common source.”

I think you’re missing the broader point here. Whether Philo based his work on an earlier source doesn’t change the fact that the gospel writers used Philo. So the fact that Philo adapted someone or something else is irrelevant. Secondly, just because later writers (like the gospel writers) didn’t use Philo’s ideas in precisely the same way does not mean they didn’t adapt it. It simply means they went another way with it. At any rate, we KNOW they did in fact borrow from Philo as some passages are lifted verbatim, as I said in my piece.

Paul: “And lastly, other than the agnostic scholar Bart Ehrman, Daniel spends most of this post filling it with arguments and quotes that come primarily from thinkers that are called “mythicists”.

Come on Paul. This is just untruth and I think you know that. In fact Remsburg was the only mythicist quoted and he was quoted not to support any mythicist argument (again, I’m NOT a mythicist). Rather, it was quoted to convey the lack of independent corroboration of the extraordinary events narrated in the gospels that we would expect to find if they were historical. And Remsburg’s work has stood the test of time; no one has refuted it. The majority simply disagrees with the conclusions he drew, but his findings remain authoritative (which is why his works are still referenced).

Paul: “A lot of Carrier’s (and some of Daniel’s) arguments focus on the idea that the Jews were expecting a Messiah to come, be divine, die, and resurrect. If this were true, then one can say that Christianity was born out of this expectation, and that early Christians forced this idea on a random preacher, Jesus, when he never would have intended that.”

Nothing in my piece suggested that. In fact I stated just the opposite: “While the dying-and-rising god motif was certainly prevalent in the ancient world, there was no such messianic expectation of this in Jewish thought.” Paul, I’m aware that Carrier pushes this line of inquiry past its boiling point and why it would be corroborative for his views, but I do not hold his views nor did I emphasize his views in my piece. The opposite in fact.

Also, while there may not have been any messianic expectation of this in Judaism, the motif of phantasmal beings appearing to people WAS VERY prevalent and suffused ancient literature; from pagan myths to pagan poets to pagan novels to pagan philosophers, all are replete with accounts of gods appearing to humans in human form. The visions described by Paul would not seem at all out of place in the pagan literature which preceded it.

Paul: “And lastly, Daniel brings up some of the crazy supernatural things that two of the Gospels talk about at Jesus’ death, that no other Gospel mentions and no one else in the New Testament references: the sky turning dark (Mark), an earthquake, dead people rising, the curtain in the temple being torn in two (all these are in Matthew). I’ll be honest with him: I have no idea.”

The idea is that these were literary inventions. The ones I mention are just a few of the many elements to gospel narratives we can say are demonstrably ahistorical, mythologized, euhemerized, fictionalized material. Both nativities, for instance, Mark’s trial before the Sanhedrin, an alleged eclipse which could not have happened at that time of year, all kinds of geographical and legal errors. Then there are the absurdities of corpses crawling out of their graves and swarming down to Jerusalem, Jesus riding on two animals at once because Matthew misunderstood a poetic coupling in Psalms, etc., etc. Several white papers, essays and books have been devoted to these and other topics.

So if you want to hold up the resurrection as the one demonstrably non-metaphorical, non-literarily motivated infusion of the texts, please be my guest, but I simply don’t find that convincing and more importantly it cannot be established on historical-critical grounds.

Paul: “In Daniel’s post, he says that Christians “forged” Josephus.”

Huh? No, I didn’t. Look back at my piece.

Paul: “There is no evidence that there was blatant, widespread “forgery” of texts as Daniel puts it.”

I don’t put it that way. The term ‘forge’ or ‘forgery’ does not appear once in my piece. As you note, it was widely traditional for ancient writers to borrow from and adapt other sources. I said nothing more in my piece, only that this reduces our confidence, for historical-critical reasons, as it’s difficult to place independent attestation.

Again see: H-C method:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_method

Regarding your brief section on Tacitus, I don’t see the point you’re trying to make or the reason for its inclusion. Perhaps you could elaborate.

Paul: “Once again, I think Daniel is imposing wrong standards on the Bible, unable to shake the fog of modernist thinking from his assessment of these texts.”

Nope. I’m simply approaching them according to the historical method, i.e., the method all critical scholars in the field approach ancient texts. Nothing more, nothing less.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_method

Paul: “And lastly, Daniel says that the texts went through “centuries” of edits and revisions. This is severely misleading.”

How is this severely misleading? You don’t specify. You may disagree as to the degree of these changes and how important they are to the Christian faith, but I was not misleading in the least. Ehrman and others have written books devoted entirely to this topic. He is always quick to point out that the vast majority of mss discrepancies are trivial copy errors. (It’s usually the first caveat he offers when he talks about it.)

But are there redactions arising from theological and ideological imperative as well? Absolutely. There are many examples. What’s more, the farther back we go the more variants that appear. This is important because we don’t have the originals. Most of the 5,800 copies (91%) come from *after the 10th century*. I repeat, after 1000 CE (just ~500 predate the 10th century). As a quick example, the first complete copy of Mark comes from the year ~350 CE, *280 years after the autographic mss*. So again, we can’t say with certainty what we read today is or is not a variant.

(I’m also not alluding to a “Dan Brown conspiracy situation”, whatever that means.)

Paul: “And hardly any of these variants are of any doctrinal or theological import at any level.”

Really? I suppose it may depend on what you consider important. If you don’t think the ending to Mark’s (the earliest) gospel, or the story of the adulterer woman in John are important then that’s your opinion. I happen to think they are very important. In the case of Mark we have discovered 5 or so other endings that were not present in the original mss. Canonizers (read: humans) simply chose the ending they liked best. Or take the doctrine of the Trinity, as usually read from I John 5:7, which does not appear in our earliest of Greek mss. Again, if you think these unimportant, so be it.

Regarding your E.P. Sanders quote, one might also want to consider the panoply of other ideologies for which men have believed deeply and even fought and died for, from Muslim bombers to the Tibetan Buddhist uprisings to…just about every major religion known to history. Sincerity of belief does not guarantee correctness of belief.

Paul: “Contrary to Daniel’s assertion, there’s no such thing as a 1st century letter to the Laodiceans.”

The reference to the Laodiceans letter is in Colossians 4:16, as you note. This letter is lost to us but since it is referenced by Paul I’m not sure why you are saying “there’s no such thing”.

Paul: “Christopher Hitchens once said that the fact that women (people who could not have even testified in court at that time) were recorded as the first witnesses to the Resurrection (in every Gospel account, by the way), convinced him that something had to have happened on that Easter morning.”

Christopher Hitchens was not a biblical scholar. The female testimony defense is common but is actually unfounded. Women were widely accepted as witnesses in Jewish, Roman and Greek courts for all manner of testimony and were often used as sources for historical information by Greco-Roman historians. It is neither absurd nor unusual that women are present in the resurrection narratives.

“being a Christian does not necessarily mean that you think every other religion or religious experience is wrong–it’s just that whenever those religion disagree with Christianity, we think Christianity is right and they are incorrect.”

All joking aside, what a coincidence. 😉

Paul: “But to Daniel’s point [about Sathya Sai Baba], there are so many variable here that make this fundamentally different. Christianity is still an utterly unique historical occurrence, with no predecessor or antecedent. There is simply no similar analogy one can find.”

Paul, they’re ALL different. All religions have differences. That’s the point. That’s why Christianity is not called Judaism and why Tibetan Buddhism is not called Shingon. The point is that we can observe clear similarities across various mythologies. (It’s in fact what gave rise to comparative mythology.) Every religion has its unique elements, and every religion has distinct, traceable influences from earlier or extant cultural motifs and religions. It’s called syncretism, and Christianity was one of several religions which fused its own elements with the broader Hellenism of the time. Basic stuff, really.

When it comes down to it, you simply find the Christian narrative more compelling than the other narratives, and you have faith that those of Sathya Sai Baba are false. Just like the adherents to all the others find their narrative more compelling and affirm their creeds based on faith. And again, what a coincidence that the religion of prominence in the culture you were raised in just happens to be the ‘correct’ one. I understand your reasons for believing it, but I simply do not find the evidence nor the narrative as compelling as you seem to.

Paul: “Ultimately, I do not think Daniel’s reconstruction is consonant with anything looking like the conclusions of mainstream scholars past and present.”

I can only shake my head in bewilderment at this point. Paul, what exactly do you think is the secular view? My statements on the explanation of the New Testament narratives is actually a *distillate of Ehrman’s conclusions*. He and other scholars have stated *precisely* the same conclusions I do in their books, lectures and debates. See Ehrman below. Please skip to 1:31:00 in the link below.

So quite to the contrary, I have stated nothing “left-field” or out of the ordinary. I understand why you would want to think that, because those conclusions are very different from the ones you have drawn. But to caricature my conclusions as fringe or outside of the mainstream secular view is disingenuous.

Lastly, I look forward to reading the NT Wright piece you emphasize and to your next piece in the series.

Best,

– Daniel

P.S. The title of this post sounds way too much like the “gatekeeper” mentality, but I digress.

LikeLike

On a related note, it’s awesome to find someone who finds these things as interesting as I do. This has been a very enjoyable dialogue and learning experience and for that I thank you Paul.

– Daniel

LikeLike

Ditto, my friend. Ditto.

LikeLike

FWIW, this is by far the most misleading part of your piece:

“Daniel seems to have a conception of “source” that thinks it only can be something later added. But when scholars say that there are many “sources” behind the text, they are often referring to it in the same way that Mark is a “source” for Matthew and Luke: an earlier tradition or piece of writing that is present as the main new piece is being written. (Perhaps Daniel is talking about a “redaction”? That would be a later addition, though textual critics are quite well aware of what sections of Scripture those are, and they are nearly all inconsequential theologically.)”

I’m not sure what you’re getting at in the first part (i.e., I’m aware of the difference between ‘source’ and ‘redaction’), but textual critics are only “well aware” of *some* redactions or variants by comparing later with earlier manuscripts. And what are our earliest mss? As I stated previously, most post-date 1000 CE. And we have none of the originals. So the only way we can identify variants is by cross examination with our earliest mss, but this tells us nothing of the variants which may have appeared in the several centuries *before* those earliest mss. And again, the farther back we go, the more variants we see (as would be expected from what we know of scribal practice and tradition before and during the rise of Christianity).

I also gave a few examples of what might certainly not be considered “inconsequential” from a theological standpoint.

Honestly, a lot of this post reads like damage control. “Yes these are problems, but it’s not really that bad, I promise.” Obviously, I think these things matter a lot. You may not. But I don’t think we should be misleading in the presentation of what is known to current scholarship. I was careful not to overstate or overrepresent and I feel like some of this post adopts a “gatekeeping” mentality and damage control. For example, I think best practice would be to list some examples of variants which may or may not have theological import (as I did) and allow the reader to decide. Present the facts and let the reader form his or her own conclusions (which may end up different from the author’s, which is perfectly fine).

– Daniel

LikeLike

Daniel, with all due respect, the more you talk about this, it betrays that you really don’t know much about this. I really have studied this under people that have done this work, and I’ve read the primary texts involved in this study. you really just seem to be regurgitating stuff from websites and blogs.

I’m not simply saying, “Daniel’s right, but it’s not that bad!” I’m saying you’re absolutely wrong on this point. when you talk about manuscripts that date after 1000, you’re talking about entire New Testaments. We have many thousands of earlier fragments and quotes and other writings, dating all the way back to the 2nd century. and guess what? They look remarkably the same as those post 1000 mss.

really? You count the story of the adulterous woman or the woman at the well as “doctrinal”? even the ending of mark, other than the snake stuff, is relatively benign. and still, early church leaders were very well aware of mark’s disputed ending. either way, you can not point to any manuscript variant that was either the cause or the “magical solution that just randomly appeared out of nowhere” to any aficionado dispute in early Christianity. Really: you think those very few chunks of text were formative at all to early Christianity? the adulterous woman, the woman at the well, and the last chapter of John are just good stories that continues circulating after the texts were written and so they added that in.

there is no line of the Apostles Creed that you could say is based on a textual variant. really. You betray a profound ignorance of manuscript variance by saying that even any statistically significant amount of them have to do with creating or eliminating doctrine. to that you might say that ” of course! Because they destroyed all the other ones” or ” all the major variations we’re done before the end of the 1st century”, but then you would be arguing from silence, and arguing from your own random, unbased assumption about how Christianity developed– an addition for which there is no evidence or basis.

you really need to look into the methods and conclusions of textual criticism. look into what the textual variants actually are. Don’t just assume variant = no integrity. First see what they are. Read that metzger and ehrman book. They really would just shake their heads if they read your comment above.

I’m sure you know this, but remember, the New Testament is the most well attested piece of ancient writing that we have. we have the most copies for it, from the closest to the original writings, then we do for any other ancient piece of writing. and even in the vast overabundance of manuscript evidence that we have–relative to other ancient writings– there is a massive and profound coherence to all of them. They all have variants, yes, but scribal error is the culprit almost always the culprit. Attempts to make the text clearer (but still faithful to the original) is the next. there is absolutely no evidence that Christianity was “formed” or even shaped by changing texts. if you wants to assume as much, fine, but know that you are getting into speculation, not accessing facts.

oh, & I transcribed this comment over voice on my phone. so sorry for the lack of proper capitalization and probable misspellings. just sound it out.

LikeLike

honestly, I’m not trying to twist anything. whereas with other points in this discussion, I am not challenging your facts but merely your interpretation, this is not one of those times. You are simply wrong about the facts. I promise you. I’m not trying to be mean or brash or arrogant. I’m simply yelling you you’re wrong. It doesn’t mean you have to accept the writings as authoritative for your life. But your understanding of this is indeed wrong.

LikeLike

Paul: “with all due respect, the more you talk about this, it betrays that you really don’t know much about this”, “You betray a profound ignorance”

Seriously? You’re right. I’m not sure why I entered into this discussion to begin with. I should probably stop making things up as I go along because that’s clearly what I’ve been doing.

Cut the arrogance and snide hand-waving Paul. I’ve said nothing Ehrman would disagree with. Most of what I discuss is common knowledge and is almost a direct transcription from his books!

Again, I’m not saying the variants definitely have great import, I’m saying let the reader decide. I’m aware that the biblical texts are the most manuscript-heavy body of literature we have and that there is a relatively consistent textual tradition from antiquity, but there is a limit beyond which we cannot peer. And that is because the majority of our mss date far later than their time of origin. We simply do not know how different our earliest mss are from the autographs. We don’t know. And the time of greatest volatility and the broadest disagreements within the Christian faith was the first three centuries, the time when we have the least mss fragments and few complete manuscripts of the canonical texts.

Given this situation, yes, everyone is free to draw his or her conclusions. Ehrman concluded that if the words were not preserved and we don’t have the originals then what does it mean to say they are reliable? Ehrman concluded that the texts were never inspired by God in the first place. I have many other reasons for rejecting divine inspiration but that is Ehrman’s conclusion.

LikeLike

Eh….i wouldn’t be so fast to say that. I’ve read ehrman’s textbook on textual criticism, and he has a deep optimism about how close we can get. And you’re understating how many early manuscripts we have or even hour this process works. Open any greek NT. You’ll find every major variant marked and the level of confidence we have in the voice made by the editors. And yeah, i do think you’re simply misunderstanding some of the things ehrman says, or taking them much further than he would. Ask that kelli girl on Facebook, if you want. I’m very confident she would say as well that you’re misunderstanding the specifics of this issue.

LikeLike

And remember, nearly the entire New Testament exists in manuscripts dated to before 300CE. And we have entire major codices that exist from before the mid-400s. We have a very good base from which to compare things. We’re not talking about the Odyssey, or anything, which only has a few manuscripts, they’re all dated way apart and far after the original writing. Or something like that. To think that the main work of text criticism happens only on post-1000CE manuscripts just doesn’t understand how this process works.

LikeLike

And I don’t doubt you’ve done what is normally due diligence. I don’t think you’re pulling stuff out of nowhere. This is just far more complicated than watching a few YouTube debates and reading a few blog posts about/by more or less one guy can explain. Actually reading the variants themselves, going through the method, seeing what normally happens and how these variants arise and the “families” of variants that exist and how they persist and move and evolve is fascinating, and ultimately, paints a different picture than you seem to think is really there.

LikeLike

Paul,

I’m neither overstating or understating the numbers. In fact I provided exact figures in a comment above:

Of the extant Greek mss (the most relevant to textual critics), we have ~5,800 copies, and 91% of them come from after the 10th century; just a little over 500 (9%) predate the 10th century. And not all of these are complete and exist only in fragments.

http://danielbwallace.com/2012/05/01/the-bart-ehrman-blog-and-the-reliability-of-the-new-testament-text/

D. Wallace is a Christian (read: non-secular) scholar. I suppose you’ll tell me next that he doesn’t understand the process as well as you do either.

“This is just far more complicated than watching a few YouTube debates and reading a few blog posts.”

I agree. You still haven’t shown something I’ve written to be inaccurate or faulty. You simply disagree with the conclusions I’ve come to. Paul, you’re trying very hard to discredit me, but you’ll have to do better than condescension.

– Daniel

LikeLike

Wallace even quotes Ehrman as saying:

“For practical reasons, New Testament scholars proceed as if we do actually know what Mark wrote, or Paul, or the author of 1 Peter. And if I had to guess, my guess would be that in most cases we can probably get close to what the author wrote. But the dim reality is that we really don’t have any way to know for sure.”

“We simply create a little fiction in our minds that we are reading the actual words of Mark, or Paul, or 1 Peter, and get on with the business of interpretation. It’s a harmless fiction…”

Now you tell me if what I’ve written comports with that or is instead a huge stretch from Ehrman’s conclusions.

Hint: More empty hand-waving won’t work.

– Daniel

LikeLike

Haha. Testy this morning, aren’t we?

I’m sorry if it seemed that I was saying we could know with 100% certainty the specific words of the original, or that Ehrman thinks that. You’re still overstating what he says, though. He says (1) we can’t know the “exact wording” (which no biblical scholar would say anyway), (2) we can probably get really close, and (3) the “fiction” one believes in order to not be paralyzed by even the modicum of uncertainty we face is, ultimately, “harmless”. Harmless to what? He doesn’t say, but building off of what I know and have read by him, and what Kelli was saying on Facebook the past few days, I think that he’s saying that our confident “moving forward” in reading the text is harmless to our interpreting of the text. I don’t know that Ehrman has ever said in any forum that there is evidence of ANY “tampering” with the substance of the texts, nor do I know of him ever saying that we can’t be confident enough in the basic contours of the substance of the writings in order to AT LEAST reconstruct what the earliest Christians ACTUALLY believed. Kelli even said that he thinks that the NT manuscripts are in fact the most reliable source for details about Christ, his life, teaching, and early beliefs about him. He is only saying that it bothers him that we can’t be 100% sure. And not biblical scholar says this anyway.

As Wallace put it: “that’s a far cry from saying that we don’t have probability on our side. And for him not to divulge how scholars go about raising their level of confidence regarding the original wording, while simultaneously speaking in generalities about what we can’t know for sure, is disingenuous.”

What Wallace says that Ehrman isn’t “divulging” is EXACTLY the items I’m saying you’re ignorant of and that play a big difference in this discussion. It’s the same thing as you thinking people need to be conversant in the Scientific Method before criticizing the limits and failings of science. That is a substantive, factual issue that plays apart here.

This is the simple reality, that you seem so dead set on refusing, no matter the facts or method: “Most New Testament scholars still proceed with the belief that we have in all essentials and most particulars recovered the original text. To be sure, there are some skeptics who would call our enterprise ‘a little fiction’ but this is by no means the majority.”

Did you actually read Wallace’s post? What do you find off with it? Do you really think he’s saying the same thing as you? Because I feel he is speaking worlds away from you. He’s certainly speaking to my perspective, at least.

LikeLike

Paul,

I’m aware that Wallace and Ehrman do not agree to the extent of the reliability of the texts and Wallace does not hold to my conclusions. I don’t think that I am stretching what Ehrman is saying, but let’s just leave that aside because we clearly disagree there.

For the record, I do like where you say that no variant has import for any line of the Apostles’ Creed. I’ve never thought about it that way before. I think you’re right about that.

I suppose in a way some of this is a rearguard conversation about the accuracy of textual tradition, when the more important discussion is whether the originals were historically accurate in the first place. We can use the historical method to adjudicate to a point, but it’s still mired in probabilities. The lack of independent attestation casts doubt on the historicity of several elements of the gospels, but there are certainly some kernels of history embedded therin. The extent to which they’ve been euhemerized seems to be the core issue, and this is a difficult question for history to pierce. But it does seem to me the more important one.

– Daniel

LikeLike

“For the record, I do like where you say that no variant has import for any line of the Apostles’ Creed. I’ve never thought about it that way before. I think you’re right about that.”