If I’ve learned anything the past few years, it’s that Evangelical Fundamentalism is absolutely right: as I’ve embraced more and more what conservatives often label a “liberal” view of the Bible, it really has negatively affected my spiritual and devotional life.

When you think the Bible is itself the “infallible, inerrant, Word of God”–when you think that the precise words themselves hold a magical power–you do approach the Bible with a greater amount of awe, respect, and mysticism. I’ve written before how it wasn’t until college that I read any of the Gospels on my own, because I had this fear of reading the “literal, unfiltered” words of Jesus. They seemed so big and other-worldly to me.

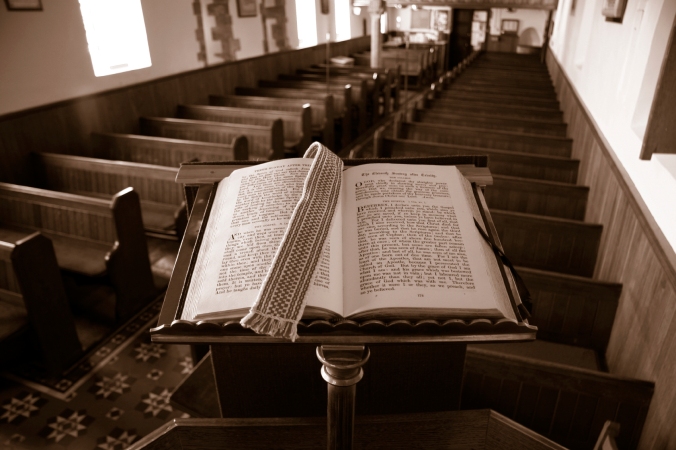

I’ve loved the Bible my whole life. I still have the first Bible I was ever given as a child. I still vividly remember the evening on my parent’s bed after they had read a Psalm that had been stuck in the middle of the stories about David that it finally clicked for me that the Bible wasn’t just narratives, but also poems and other kinds of writing.

My Southern Baptist upbringing has got it engrained in me that my entire spiritual and devotional life should revolve around this book. No matter how much I tell myself otherwise, something in me always has (and always will) “evaluate” my spiritual health by how I engage the Scriptures, in both quantity and quality.

But my senior year of college, I read Francis Collins’ The Language of God, and my lifelong war against Darwinian Evolution had ended; and with it, the cracks began to show in my view of the Bible. If my literalistic view of the Bible had been wrong, what alternative was there? And so on this point, Evangelicalism was correct: Evolution was indeed my gateway drug into a more human view of the Scriptures.

This is one reason why things were able to change so radically for me upon entering seminary. Spending time with the people, readings, and theology that I did, I found that the Evangelical structures around which I had formed my ideas about the Bible were untenable. They weren’t based on reality, but rather an illusion, a safety net, a hoped-for world in which Christianity had its own set of “facts” and most of its time was spent playing defense against all those that would try and shatter the stained glass sepulcher in which we slept.

But shatter it did.

Now, I hate actually saying this out loud because I know the vultures of Evangelicalism are circling overhead, ready to pounce on any “I told you so” in how one’s view of the Bible really does ripple out into the rest of their spiritual life. I so hate admitting this, but it’s been hard ever since my views started to shift. It’s been a war to stay connected to my beloved Scriptures. With all the scholarship behind these texts swirling in my mind, it’s been difficult to engage the words spiritually. And I’ve been fighting to figure it out for the past six years. I’m weary. I’m tired.

But it’s true. A “human” Bible can feel very much like a desert, and the safety of a more typical “Evangelical” view of the Scriptures can seem like an oasis. It’s hard to look at the pages of Scripture and simply know that God meets us there. The “magic” is not simplistic, clear, easy, and self-evident.

I’ve actually found myself in these incredibly bizarre moments this past year while walking down the street, driving in my car, or laying in my bed when I feel that I could make the willful decision to fall back into the arms of a fundamentalistic view of the Bible; to simply assume that the “hard” things about the Bible have been overcome by a God who stands outside of the messiness of history and overcomes those limits. I hear the whispers:

So what if there’s no historical evidence for this or that thing in the Bible? So what if there’s actually tons of evidence against it? So what if this part of the Bible contradicts this other? It’s too hard to fit it all together. Just let go. You will not surely die.

But in the end, I always remember the desert oasis is a mirage. The name that’s been imprinted upon my heart as the people of God–Israel–means “they wrestle with God”. And the first one to ever receive that name was one who spent his life with a limp.

There is no life with God without limping and chronic pain. For we have been granted to wrestle with God. This is our lot and our blessing.

But this past semester, I think I found a respite from my running, however brief or fleeting it proves to be.

I got to preach.

More than any systematic or biblical theological course I’ve taken, more than any book or speaker I’ve engaged, the thing that has helped me most to re-engage the Bible, and understand a way of relating to it is this past semester’s preaching class.

We had incredible readings in this course, we all got to sit under amazing preaching from one another, and we had to go out and listen to sermons offered by others throughout the world from diverse perspectives, backgrounds, and theologies.

And I realized that it’s here, in the church’s preaching, that Christianity’s uniqueness is truly known. It’s where the Bible collides with real, messy life. It’s where it becomes alive and vibrant. It’s where the Spirit makes God known to us. It’s where–to be frank–archaeology, scholarship, textual criticism, and redaction theory be damned. Those things are important, but in preaching, we have more pressing matters to attend to, and the Scriptures are made alive to us by the Spirit.

This has reminded me that I don’t have to fall back into the cocoon of Evangelicalism’s false security. And neither do you.

I’ve been reminded of the most important thing about our God and how he relates to us: He speaks. He wants to be known. He reveals. The Scripture is alive not because of any qualities inherent to itself, but because of the God who uses those words at his freedom and choosing to reveal himself to us.

And you know what? No matter the scholarly issues behind the text, this is his chosen primary means of making himself known. The Bible is not first or primary. God and his desire to communicate himself comes first. The Scriptures is a means to that greater present reality.

And as I myself was able to preach, sit under such a great diversity of preaching, and read amazing words articulating beautiful theologies of preaching (and being forced to articulate my own), I feel like for the first time in a long time I was able to see “behind” the words to see the Word. And in this, I find myself with a renewed confidence in our “family stories”.

I’ve been able, at least for right now, to sit in the beautiful tension between a messy set of assembled human texts that bear the indelible marks and scars of their culture and history, and the doggedly communicative God that breathes through those words, both then and now.

Therefore sisters and brothers, let us take and read–for He speaks.

Well said: “No matter the scholarly issues behind the text, this is his chosen primary means of making himself known. The Bible is not first or primary. God and his desire to communicate himself comes first.” I had a similar realization in seminary and recently blogged about it here: http://faith-seeking-understanding.org/2014/06/27/god-breathing-on-us/

LikeLike

An interesting study is how Jesus quoted or referred to scripture – the Old Testament, and the lattitude (or not) that he showed to holy writ.

LikeLike

Oh yeah. Jesus would fail most any modern biblical interpretation seminary course, with how he (and other New Testament writers) treated the a Old Testament.

LikeLike

I too have come form a similar theological stable and really appreciated your turn of phrase and the way you reminded me that the tension is well ok. Cheers. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: A Sermon I Got to Preach on Isaiah 61 [VIDEO] | the long way home | Prodigal Paul