We are now, finally, after a long time, starting our series on Male Feminist Theology. This is the first of many posts to come.

We are now, finally, after a long time, starting our series on Male Feminist Theology. This is the first of many posts to come.

God is infinitely complex and beyond our articulations. It’s impossible to hold in our minds at any one time all the different paradoxical truths about who God is. (As I’ve described before) depending on the particular context, concerns, or questions at hand, there are different truths about God we should dwell on and emphasize a little more for that moment.

In our day and place, I think one of the biggest issues facing the church is our treatment of women, so this post will focus on what truths about God that we (especially men) should emphasize and hold in our minds when moving forward on this issue.

As a male feminist, I believe that God is a God that suffers in his Divine nature and character from eternity past. I’ve articulated (and debated; had guests posts about; posted quotes about) this belief of mine before, and I think it is especially fruitful when discussing how God relates towards a world that is broken in its treatment of women.

This idea that God suffers—in his very nature—has been proposed before by other theologians throughout the Church’s history, and the primary critique of it is that it sounds really close to what’s called an “Open” or “Process” view of God in which the God who is biblically described as “never changing” is subjected to the cataclysmic change of suffering.

But the view I’m offering here is not an Open view. Rather, I’m saying that God’s nature and work (an expression of this nature) inherently has a telos–it has a goal towards which it is moving, and this “movement” could be no other way. This movement (or “story”, if you prefer) is who God has been, is, and forever will be.

What is this “shape” of God’s nature? It is suffering unto life and shalom. Shalom is the Hebrew work describing what it’s like for the world to be knit back together again. Therefore I believe God’s very nature is one that begins in suffering and leads to new life within itself–not unlike the female process of childbirth.

This Divine “shape” and “movement” is what brings about all those super fancy theological words used since the Church’s earliest days to describe what’s going on in the Trinity: begetting, procession, perichoresis. This movement from suffering to life is also the source of God’s creative, “new life” impulses: Creation, election, Incarnation, Resurrection, and New Creation.

Some critics of this view say that if this is God’s Nature, it doesn’t hold any resources for liberating women from their oppression. In their essay, “For God So Loved the World?” Joanne Carlson Brown and Rebecca Parker write:

The advent of the Suffering God changes the entire face of theology, but it does not necessarily offer liberation for those who suffer. [This] image of God still produces the same answers to the question, How shall I interpret and respond to the suffering that occurs in my life? And the answer again is, Patiently endure; suffering will lead to greater life.

But this is why we need to say that God’s suffering nature is not “simply” suffering—it is “Suffering-Unto-Shalom”. We must not say one without the other. This God seeks to bring all things into Communion and solidarity with her own telos of life and shalom. Later in the same essay, Brown and Parker say this:

It is not acceptance of suffering that gives life; it is commitment to life that gives life. The question, moreover, is not, Am I willing to suffer? but Do I desire fully to live? This distinction is subtle and, to some, specious, but in the end it makes a great difference in how people interpret and respond to suffering. If you believe that acceptance of suffering gives life, then your resources for confronting perpetrators of violence and abuse will be numbed.

This is precisely why, when thinking of God while considering our sisters in the world, we ought to hold to a God that experiences suffering and death within himself but does not keep it there. In the Divine alchemy, injustice is turned into justice; violence into peace; death into life. This means that God’s own life is being experienced while women experience injustice and when others fight against the injustice. Both of these experiences are God’s own life being displayed in the world.

For a male feminist, theology must start from this place where the suffering of women is not something “foreign” to the otherwise distant, Kingly God. The conception of God I’m emphasizing here cannot be identified with patriarchal identifications of power at the expense and marginalization of others.

A male feminist theology must begin with a God who—within her nature—experiences solidarity with women, not “merely” or “incidentally” as a result of other subsequent acts or sovereign decisions, but then moves–both within himself and in the world–towards life and wholeness.

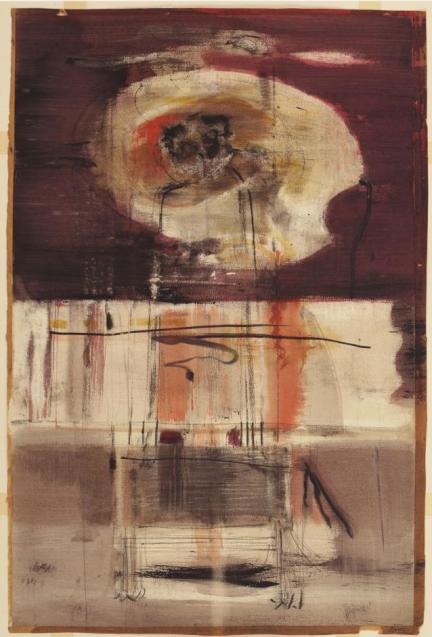

[image credit: “Untitled” by Rothko]

Pingback: Male Feminist Theology: The Dying & Rising Christ | Prodigal Paul | the long way home

Here are some possibilities your theology leaves open:

Maybe making promises to save sinners was just a phase for the less than perfect God who hasn’t reached his telos of perfection. Maybe the decision to save sinners was just a transient step along the path, one that can be undone because God can “move” beyond it (just as he moves beyond suffering). If God’s “nature” can suffer, so can his morality. Maybe during a severe bought of suffering, God moves away from being faithful to becoming unfaithful. Why not? Because Scripture said he can’t? Maybe Scripture was just revealed at T1 of suffering, but at T2 of suffering and moving, God is completely different. Why not?

LikeLike

I think a little liberation theology is in order here: “How is the discourse of a suffering God in the end anything more than a sublime duplication of human suffering and human powerlessness? How does the discourse about suffering in God or about suffering between God and God not lead to an eternalization of suffering? Do not God and humanity end up subsumed under a quasimystical universalization of suffering that finally cuts off the counterimpulse resisting injustice? Or is there not perhaps too much Hegel at work here, that is, too much reduction of suffering to its concept? Finally, I have always wondered whether or not there is in this discourse about a suffering God something like a secret aestheticization of suffering at work.” -Johannes Baptist Metz, A Passion for God, p. 70.

LikeLike

Nathaniel – how do you find this stuff??

LikeLike

I believe I found the Metz quote in one of Thomas Weinandy’s books. When I found out that there was a liberation theologian who defended divine impassibility I looked up the quote and saved it in a word document. When I find really good quotes, especially truths coming from unexpected places, I try to write them down so that I can use them when the occasion arises. For instance, I have a five page word document of quotations from the church fathers asserting divine simplicity.

LikeLike

Just in case someone thinks Aquinas made it all up.

LikeLike

Each of you raise the most understandable and immediate objections to Divine Suffering, both of which I at least tried to give a passing response to in the post.

Bob, my view rejects Divine Temporal Complexity. This Suffering-Unto-Shalom is the Divine Nature, and we know this because every form of revelation demonstrates this. There is no T1 and T2. God is at all times Suffering-Unto-Shalom. He is not suffering in one place and shalom another. Further, none of the hypothetical questions you raise are resolved any more in the more static, Platonic view of God you seem to be defending. Especially your line about “Why not? Because Scripture said he can’t?” Firstly, it is an article of faith that God does not change. Even though Scripture says (in shockingly few places) that God does not change, that could still be his Divine prerogative only in this revealed hypothetical “T1”. In other words, he might not change “for now”. Secondly, the center of our knowledge of God is Jesus, not Scripture, and I root my belief in a never-changing, suffering God in Christ and the Cross. The controlling question for me is this: is the Cross something ADDED to the Divine experience, or a REVELATION thereof? I of course choose the latter. So yes, we can be confident in God’s unchanging, suffering nature that enfolds ALL our reality and brokenness.

Nathanael, that really is a powerful quote, and I resonate with it deeply. That’s why I address this critique in the post. I don’t hold that God’s nature is “simply” suffering, but “Suffering-Unto-Shalom”, so that we experience our union with Christ BOTH while suffering AND when working to undo it. And while I hear the concerns about Hegel (or even Spinoza) creeping in, (while acknowledging that I think both of those guys are due a more favorable reanalysis) I would rather find my influences closer to Luther, Levenson, Jensen, Breuggemann, Moltmann, Barth, and I flirt with Orthodox views of theosis. I know Bob spends all his time with patristics and knows them inside and out, but on this topic, I find more Philo and Plato than St. Paul in their writings (though I feel Athanasius would perhaps come on board eventually).

Either way, an entirely impassible God doesn’t make any sense of the world, our lives, and God as he is revealed in both Scriptures and Jesus. Can there not be some sort of balance between an entirely Open God and an entirely Static, Unaffected God? My proposal in the post (and in the posts below) try to offer a more complex view of this than either of those extremes. But still, I’m open to more critique on this as you two are so inspired. (And Austin, you got anything?)

“Creation: a suffering world through a suffering Lord” http://wp.me/pnQ3d-1lC

“Evil & the Essence of God: a storied solution?” http://wp.me/pnQ3d-1Wa

LikeLike

My concern is that if “Suffering and Death” are “elements in the world [that] are echoes of the groans and pains of a suffering God whose essence is interwoven into his Creation” then it seems that God cannot be wholly against them. I also wonder if you escape the trap of reifying suffering into an abstract Suffering when you talk about God’s essence as “suffering to life”. To give one concrete example of my worries let’s look for a moment at the middle east. As a Reformed Christian I am in the rather uncomfortable position of having to say that the butchering of Christians in the middle east is part of God’s will, an evil which he has permitted. But, if I read you correctly, you would have to claim that this slaughter is an outworking of God’s essence in the world. Is this really what you want to say?

I also wonder if your “suffering to life” model can really account for the Bible’s depiction of God as a “God of vengeance” who will judge the world (e.g., Psalm 94). In other words, I wonder how God can judge the wicked for causing suffering if suffering is an outworking of God’s essence in the world.

LikeLike

You’re absolutely right. The biggest weakness in Divine Passibility is suffering within history, including (especially?) Christ’s own. I admit, I’m still working through this. Let me try some things on with you, and see what your take is?

Is it enough to merely reassert the Creator/Creature distinction and still hold to this belief? My intuition fears that I can’t. But in a similar way that the Imago Dei does not negate personal individuality, dignity, and integrity, but connects us with the Divine, could it be that each historical act of suffering has its own “integrity” and individual horror, while at the same time being such a shadow/echo/representation/”Image”(?) of God’s own suffering?

As I say in one of those links, human suffering is in existence due to Creation having been created “through” a Crucified and Suffering Christ. What this means is that the possibility for suffering is open (not necessitated) because of the One through whom everything was made. This attempts to maintain a distinction between Divine Suffering and human. Creation, Evil, Suffering, etc. is not (merely) an instantiation of Divine Life and Consciousness (as Spinoza would perhaps say). Again, perhaps childbirth is a good analogy? In a sense, we suffer because we have been created “through” another suffering, embodied human, but it doesn’t make our own suffering any less particular and real.

As for wrath and justice, this is why I am trying to add this telic aspect to Divine Passibility. I would say that Suffering’s EXISTENCE is due to the Divine Nature, but not its PERSISTENCE. Divine Suffering never persists in se. It is always in a (can I use the word) perichoretic movement towards life. It is a stream, a torrent, a waterfall from SUffering to Shalom. You are not participating in the Divine Life within your suffering unless you are actively working for justice, shalom, and the undoing of the suffering.

As for your last point, my first thought is the Cross. Christ becomes curse, sin, and suffering on our behalf, and yet God is Judge against him. If the Cross is the revelation of the Divine–even in his suffering and death–we see that God still judges and shows wrath against it–against himself. I’m channeling some Barthian election thoughts here. Also, here are some provocative words from Kazoh Kitmori’s incredible, pivotal work, “Theology of the Pain of God” [http://amzn.to/1OMmCvr]:

“The ‘pain’ of God reflects his will to love the object of his wrath…God who must sentence sinners to death fought with God who wishes to love them. The fact that this fighting God is not two different gods but the same God causes his pain….The Lord was unable to resolve our death without putting himself to death. God himself was broken, was wounded, suffered, because he embraced those who should not be embraced…. An absolute being without wrath can have no real pain…The pain of God is his love–this love is based on the premise of his wrath, which is absolute, inflexible reality. This the pain of God is real pain, the Lord’s wounds are real wounds….The cross is in no sense an external act of God, but an act within himself. [As Luther said,] ‘The cross was the reflection (or say rather the historic pole) of an act within Godhead. [Therefore,] the gospel was proclaimed even before the foundation of the world, as far as God is concerned.’…The question in regard to the salvation of the world, according to him, is not the relation between God and the world, or God and Satan, but the relation between GOD and GOD TO THE WORLD.”

Lastly, I’ll say two quick things. This blog series is based on a paper I already wrote for a class that I’m splitting into multiple posts. If you decide to keep up with it, I’m going to keep posting the paper with only minor edits for clarity. Don’t think I’m ignoring your helpful critiques and simply “moving on”. I’ll continue sitting with all this. Secondly, know that the theological area in which I’m most well-versed is biblical studies rather than systematics. This has the advantage of a certain level of immunity to Robert’s theological method of name-dropping (kidding, mostly), but has the disadvantage of not being as comprehensive in those who have come before me, especially from the early church and medieval thinkers. So feel free to help me with that. Thanks again for replying.

LikeLike

Paul, you wrote about God “moving.” You wrote, “Therefore I believe God’s very nature is one that begins in suffering and leads to new life within itself.” What is that besides a movement from one state to another? If God can move in that respect, why not all respects (e.g. morally)?

The Christian God is not open to the same criticism as He has perennially been confessed to be absolutely simple and immutable.

LikeLike

“If God can move in that respect, why not all respects (e.g. morally)?”

Because he has revealed himself thusly? We know the full “movement” of God from beginning to end. It cannot be anything other than what he has said it would be and as Christ is. Again, as I said, I don’t know how simply asserting simplicity and immutability prevents the same problem, as we’re all working on the same set of revealed truths.

And though I think the patristic and medieval articulations of simplicity or entirely inadequate to the complexity of Divine Ontology, at the most basic level, I still think my view holds to Divine Simplicity, especially temporal simplicity. God is at all times Suffering-Unto-Shalom. He is not Suffering in one state, and Shalomic in another. It is always Suffering-Unto-Shalom.

Yes, this is more Eastern, Hebraic, and Post-Structural rather than something that can be fit into the of type scholastic systematic scheme you would prefer and try to fit things into.

LikeLike

What do you mean by Eastern? Do you mean Eastern like Eastern Orthodox? That seems doubtful since the Greek fathers and their Byzantine heirs held to divine immutability and simplicity. Or do you mean Eastern like the Islamic Middle East or is it Eastern like Hindu and Buddhist India or Eastern like Far East (China and Japan)?

LikeLike

More like Middle-Eastern. As opposed to Western ways of thinking.

LikeLike

You do recognize that Islamic theology embraces divine immutability and simplicity and that Islamic thought was heavily influenced by Aristotle and Neo-Platonism at a formative stage, right?

Or are you talking more about Rabbinic Judaism?

LikeLike

Rabbinic Judaism, for sure.

LikeLike

Pingback: Male Feminist Theology: Table of Contents | Prodigal Paul | the long way home

Pingback: What Should a Male Feminist Think of Our Messy Bible? | Prodigal Paul | the long way home