This weekend I had the privilege of seeing the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s new exhibit Gauguin, Cézanne, Matisse: Visions of Arcadia. The exhibit showcases works exploring the idea of “Arcadia“: an idyll pastoral world envisaged in Virgil’s first major poetic work Eclogues where nymphs and fauns dwell alongside Bacchus and Pan; where human dwellers exist in peace, rest, and joy in the natural world.

(To put it simply: you can usually recognize Arcadian themes at work in a piece of art when it has naked people hanging out in nature–usually around rivers.)

This image of Arcadia, having been explored in art epochs in the past, overtook art once more right as modern art was being born, right around the turn of the 20th century. In fact, the exhibit subtly makes the argument that this image of a rural, paradisal ideal is an essential element in modern art’s development. The modernists’ dilemma–the tensions between longing and reality, finding and losing, permanence and transience, human and mythic–all find their embodiment in this Arcadian world.

The exhibit begins with excerpts from Virgil’s poetic treatment of this theme, set beside works that visualized his words. These run along one wall. On the opposing wall of this introductory hallway, there are excerpts from Stéphane Mallarmé’s modernist treatment of Arcadia, L’Apres-midi d’un Faune, accompanied by pen-and-ink drawings from Matisse that visualize his words.

The exhibit is great, but very theoretical. It works subtly and on nuance. It’s not just a bunch of pretty things thrown into a room. Instead it is a thesis–an argument–in visual form. It watches a theme develop from myth to poetry to visual art (and then from Renaissance to modern) and explores how they are all connected and converse with one another. It’s really like no other exhibit to which I’ve ever been. If you get the chance, see it.

But that’s not why I’m writing today.

Perhaps it’s because the exhibit works on such a deep level, or maybe it’s because it works at this level using art and beauty which can “get inside of us” a little more easily than logic, but either way, this exhibit awakened such busyness, anxiety, and paralyzing fear in me.

Why? Well, all I could think of while seeing these happy and free naked people hanging out by rivers was death. And death terrifies me.

Unlike the idea of “Utopia”, Arcadia is not a world of progress, politics, technology, and the accomplishments of civilization, towards which we can move as humanity. Instead, it is Eden: the world that is no more and (if we’re honest) we doubt ever was. This exhibit caused me to later explore both Virgil’s and Mallarmé’s poems myself, and in fact, Mallarmé’s opens with this very idea when speaking of Arcadia:

__________________Did I love a dream?

My doubt, mass of ancient night, ends extreme

In many a subtle branch, that remaining the true

Woods themselves, proves, alas, that I too

Offered myself, alone, as triumph, the false ideal of roses.

For Virgil’s part, his poem is so strange, as it is meant to be a picture of this ideal world, but there’s a sobriety to the piece–a sadness, even. There’s still conflict and hurt and loss and unrequited affection, but it’s in a weird way where the presence of these things doesn’t seem to spoil or affect the nature of the place. In other words, Arcadia is like a perfect, beautiful, spotless bowl, full of loss, pain, and transience–and yet, the bowl is never stained.

But you can’t see the bowl’s perfection without feeling the weight of the loss.

Every one of the paintings, it seemed, was full of such freedom and harmony with nature and the world. And yet, each of these paintings had at least one feature that was dark, somber, or even sad. Notice the face of the person behind the tree on the left side of this painting by Camille Corot (excerpt below):

The whole exhibit is built around three large pieces that show the influence of Arcadia on the modernist masters. And, we see this weightiness there as well.

In Gauguin’s Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (the header at the top of this page–full size), you see him try and bring Arcadia into the modern and real world, but it features (from right-to-left) the isolation of life from birth to death (with a lot of work and labor in the middle).

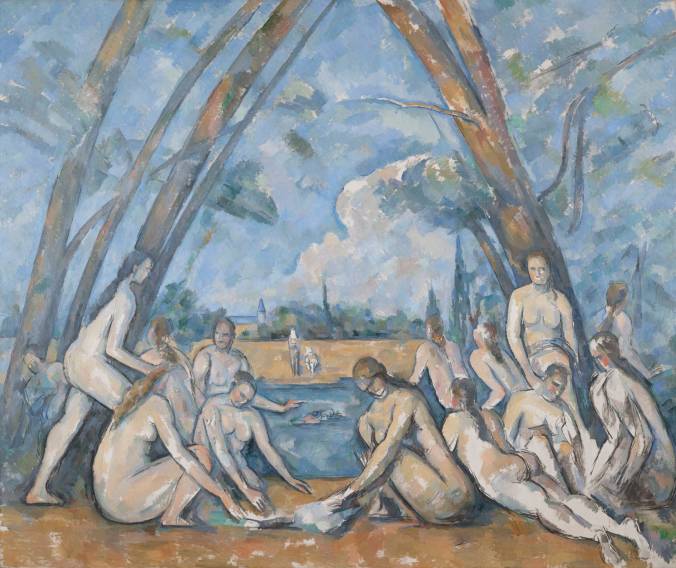

In Cezanne’s The Large Bathers (above, at the top of this post), you see this joyful, freeing scene of harmony between these women, being cleansed in nature, and yet, there seems to be sadness on all their faces, as well as a transience to the world.

And lastly, in Matisse’s Bathers by a River (below), we see how the river, this source of life and joy and cleansing is now black and home to a serpent waiting to attack.

In short, Arcadia testifies to how we engage with the source and telos of our longings: to be free, to be in harmony, to be clean–to be reconciled to all that is within us and without us. But it also highlights how we don’t have those things, we doubt we ever did, and–perhaps to a greater extent–we doubt we ever could. In both Virgil and Mallarmé, this vision of Arcadia is questioned: is it even real?

Dreams, in a long solo, so we might amuse

The beauties round about by false notes that confuse

Between itself and our credulous singing;

And create as far as love can, modulating,

The vanishing, from the common dream…

Of a sonorous, empty and monotonous line.

(Mallarmé, also see above quote)

Here’s our fear: we may get tastes and aromas of this reconciliation and rest that Arcadia represents, but in the end, how do we know it’s not all a dream?

See, while I waited to carry it out, the ash of its own accord

seized the altars with quivering flames. Let that bode well!

It means something for sure, and Hylax barks at the door.

Do I believe? Or those who love, do they create their own dreams?

(Virgil)

And worse yet, our sorrow over this loss seems to make no difference, all while our hope can only come from the very Arcadia we know not exists:

‘Is there no end to it?’ he said. ‘Love doesn’t care for this:

Love’s not sated with tears, nor the grass with streams,

the bees with clover, or the goats with leaves.’

But Gallus said sadly: ‘Still you Arcadians will sing

this tale to your hills, only Arcadians are skilled in song.

O, if one day your flutes should tell of my love,

how gently then my bones would rest (Virgil)

If only Arcadia could sing and tell of our love, then maybe our bones could rest.

This exhibit forced me to face my own mortality, but not only that. It forced me to face my uncertainty, fear, and doubt that in the end, Arcadia will never come–that my hope itself is but a dream.

At the time, the way I dealt with this anxiety, unrest, and fear was to do what I always do when I’m feeling that way: head to the Medieval art section.

But in these past few days, as the effects of the exhibit have lingered, I’ve turned to the original two poems to try and find their solution to this fear. The solutions offered at the end of their poems are quite striking (P.S. I’ve written about the converting power of poetry before).

For Virgil’s part:

‘Love conquers all: and let us give way to Love.’

Divine Muses, it will be enough for your poet to have sung

these verses, while he sits and weaves a basket of slender willow.

You will make these songs seem greatest of all to Gallus–

Gallus, for whom my love grows hour by hour,

as the green alder shoots in the freshness of spring.

Let’s rise, the shade’s often harmful to singers,

the juniper’s shade is harmful, and shade hurts the harvest.

Get home, my full-fed goats, the Evening Star is here: go home.

He trusts Love itself to be more powerful than our doubts. He recognizes there’s a part of himself that feeds off of this doubt and fear. There’s a level of comfort in doubt–in a way, it’s safe. We can occupy ourselves with little tasks while thinking our thoughts of doubt while singing our songs of distraction, longing for and loving this mythical ideal of “certainty” we might want. But in the end, Arcadia’s shade can be harmful to all that needs to grow if it stays too long. And so, at some point, we need to get up, and go home.

Mallarmé’s take?

I hold the queen!

__________O certain punishment…

________________________No, but the soul

Void of words, and this heavy body,

Succumb to noon’s proud silence slowly:

With no more ado, forgetting blasphemy, I

Must sleep, lying on the thirsty sand, and as I

Love, open my mouth to wine’s true constellation!Farewell to you, both: I go to see the shadow you have become.

Because we know that absolute certainty is fleeting, when we feel we have a hold of it, there’s almost a sense of “guilt” that sets in–terrified of the impending punishment that will result in its loss. And it’s in this reminder of Arcadia’s transience that we lose words. It’s not about arguments. It’s not about logic. We must forget our blasphemy of demanding such certitude. We must simply rest. Just as with Virgil, we must leave our visions of Arcadia and dwell in the world as it is, seeing the shadow that Eden has become.

As my pastor preached this past week, hours before I saw this exhibit, we deal with reality as it is, but hold on to a hope for the world to come (or rather, let it hold on to us).

Will my doubts and fears ever go away? Maybe not. But one thing I know and have learned: the longer I dwell in them, trying to make this Old Creation into Eden, and then–worse, perhaps–trying to make Eden into the New Creation, I will only create certain Hell in my mind and heart. We are, rather, to make this Old Creation into the New.

And for that task, there is ample hope.

Here’s to changing our vision from Arcadia to the Kingdom.

Pingback: Debates with Atheists (And Good News for Them) | the long way home

Pingback: Christians & the Art of Profanities in Art | the long way home

Pingback: Weekend Photo Challenge: Home (the one to come) | the long way home

Pingback: Change: God is Real [Guatemala, Day 4] [photo sermon] | the long way home | Prodigal Paul

Sorry it seems your pastor ruined the exhibit for you. Many of us Christians are also Naturists, and we do find idyllic spots out in nature, and we do refresh ourselves naked by rivers. This experience, just as in singing “Blessed Assurance” gives us a “foretaste of glory divine” in the New Heaven and New Earth which is coming.

LikeLike